What was it like digging wells in the late 1960's in "Upper Volta" -- what is now Burkina Faso? Read this first-hand account and instruction guide for future well diggers to find out.

The ostensible reason for going to Upper Volta in the first place was to be a puisatier, a digger of wells. More specifically , my job “was animating the local population to dig and cement large-diameter wells, and to educate the people on the health and agricultural benefits of a clean water supply”. And indeed, for two years I and my fellow well diggers organized our lives around the well digging season. My memories of the actual activity are sketchy, but somewhat refreshed by having lately gone through all of my letters home. In those letters, mostly covering the months January through June, the well digging season, I do make some effort to tell my mother about both the process and the challenges of carrying out my primary responsibility to the people of Upper Volta. Armed with that evidence I want to see if I can get to the reality of it.

First, it is important to note that in my COS documents provided by Peace Corps I am credited with "digging" 11 wells. As mentioned, my late middle aged brain has recollection of only a couple of specific wells, and those may in fact be composites of various wells, and the reality is that I dug none of them. Nevertheless, I attempt here to provide instructions, 50 years later, for future well diggers in the Sahel

How to build a well

Have the village locate a site. They may know from experience where there is likely to be water, and there will probably be village politics involved (near the chief’s compound is a likely location) and you definitely don’t want to get tangled up in them. If they want to use a dowser go ahead and pay for it, so if the well fails you cannot be blamed. Recognize that the chances of choosing a site that will hit granite at 15 feet are 50/50 and that nothing is more discouraging to the villagers than creating dry holes in the sahel- “ya wenam bala” (God’s will) only goes so far in keeping the village engaged in too many futile efforts.

Make sure that the village has identified where they will get sand and gravel for the concrete, and have them begin to amass a suitable pile of both before you begin digging. Promise the bigas candy and the women the used concrete sacks as incentives but let the chief or whomever he designates as the local leader hand them out. Remember that the sand and gravel are being swept up by hand and brought to the site in baskets on the heads of the women, and plan accordingly. You will need enough to build a mixing platform and set posts for a pulley system at the beginning of the project., and once you hit water you need to have enough on hand to pour the first couple of meters to avoid cave-ins.

Once the site has been selected hold a ceremonial kick off with all of the village elders present. This will be the one of the few times you actually do any digging or other real work, so make the most of it. The ceremony goes as follows:

You make a short speech in Mooré (just to get started and give them a laugh) and then in French to describe the project. Be sure to restate and emphasize what they have agreed to - dig the hole to specifications, gather sand and gravel-essentially all of the work, and what you will do-bring the tools and cement and ok any expenditures.

Take a piece of ½ inch re-rod, about a half meter long, and drive it in the ground at the chosen spot. Take a piece of ¼ inch re-rod, 80 centimeters long, with a loop in one end and the other end bent at 90 degrees. Put the loop over the center stake and using this crude compass trace a 160 centimeter circle in the dirt. Emphasize that this is the size and shape of the well and that the digging must not stray from this shape and size or there will not be enough cement to complete the job. This of course is a bluff. There is no way in hell that you can dig 25 or 30 feet down with dabas , picks and shovels maintaining these dimensions.

Take a shovel and pick and make a ceremonial dig. Maybe you can get each of the elders to take a spadeful just for emphasis.

Bring out the dolo that you have ordered beforehand, and sprinkle some on the well site, before sitting down with whomever the chief has invited to drink it up. Be sure to have some kola in your pocket, and bring extra gauloise to share.

After drinking too much dolo, get on your mobylette, with two or three chickens dangling by their legs from the handlebars, and weave your way slowly enough to not to blow out a tire in the potholes or run over women coming from the bas fond with canneries of water on their heads, but quickly enough to get home before the dolo headache sets in or it gets so dark that you miss your turn and end up aimlessly wandering amidst the millet fields.

The process now is for the villagers to dig the well with the specified 160 centimeter diameter until water is struck. In order to dig beyond the first meter you will have to construct a derrick over the well which combined with pulleys or block and tackle will provide the way to remove the dirt, get the diggers into the well, and once water is hit, get the mold and cement into the well.

Ideally you will be starting new wells on a regular basis, and you will spend your days during the well season repeating the above process and visiting each well site on a daily basis. In reality, half the time you will have a stomach ailment which will require you to stay close to your latrine, and several more days will be spent repairing flat tires on your mobylette or travelling to town to pick up supplies . On the two days out of the week left, one will find the villagers celebrating a birth, death, or some obscure Catholic, Protestant, or Muslim holiday. The remaining day some work might get done if it doesn’t rain or isn’t too hot. If it does rain, not only is there no work, but the sides of the well probably have caved in.

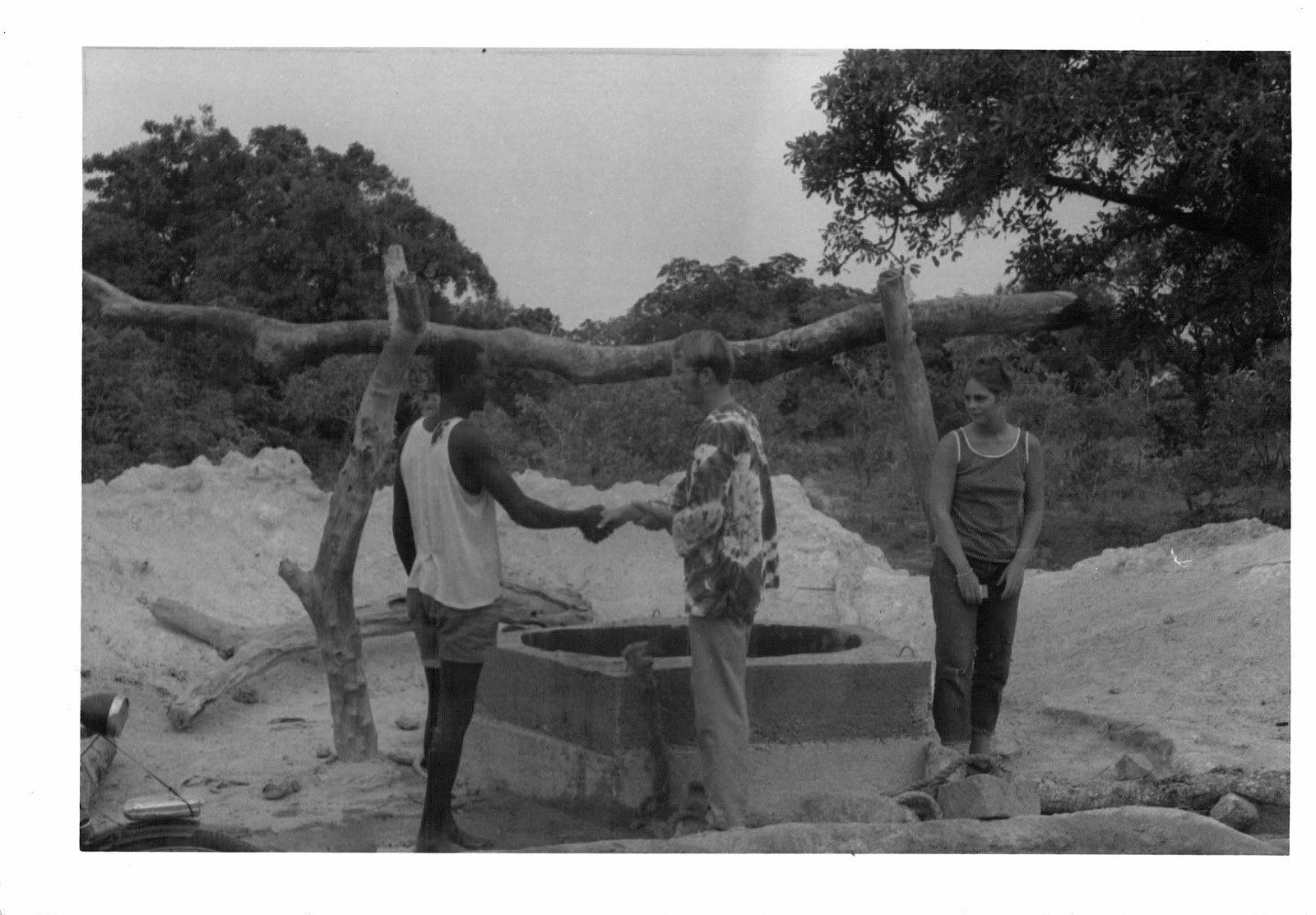

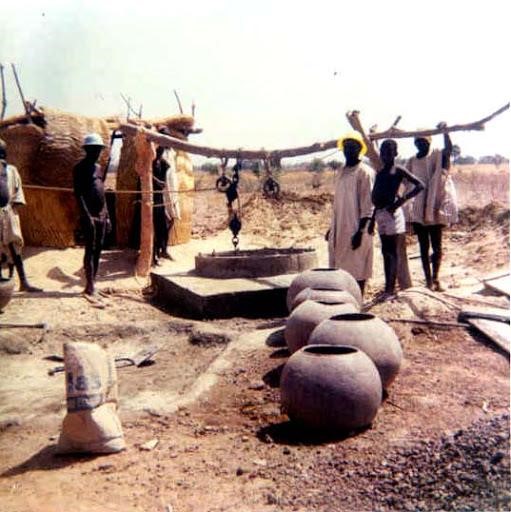

As noted, building a derrick over the well is a crucial step, and one of the few things you can do to make digging a well in the bush less hazardous than say playing NFL football without a helmet. To accomplish this have the villagers find two stout, relatively straight tree limbs with forked branches, about 6-7 feet long. Set these supports in concrete on opposite sides of the well. Find another relatively straight limb for a cross piece and lash it tightly to the forks. Attach a pulley to this cross member, run a 1 inch rope through the pulley, and tie a stick on the end of the rope. Voila!

To enter the well, you simply sit on the stick and have the workers slowly lower you in.

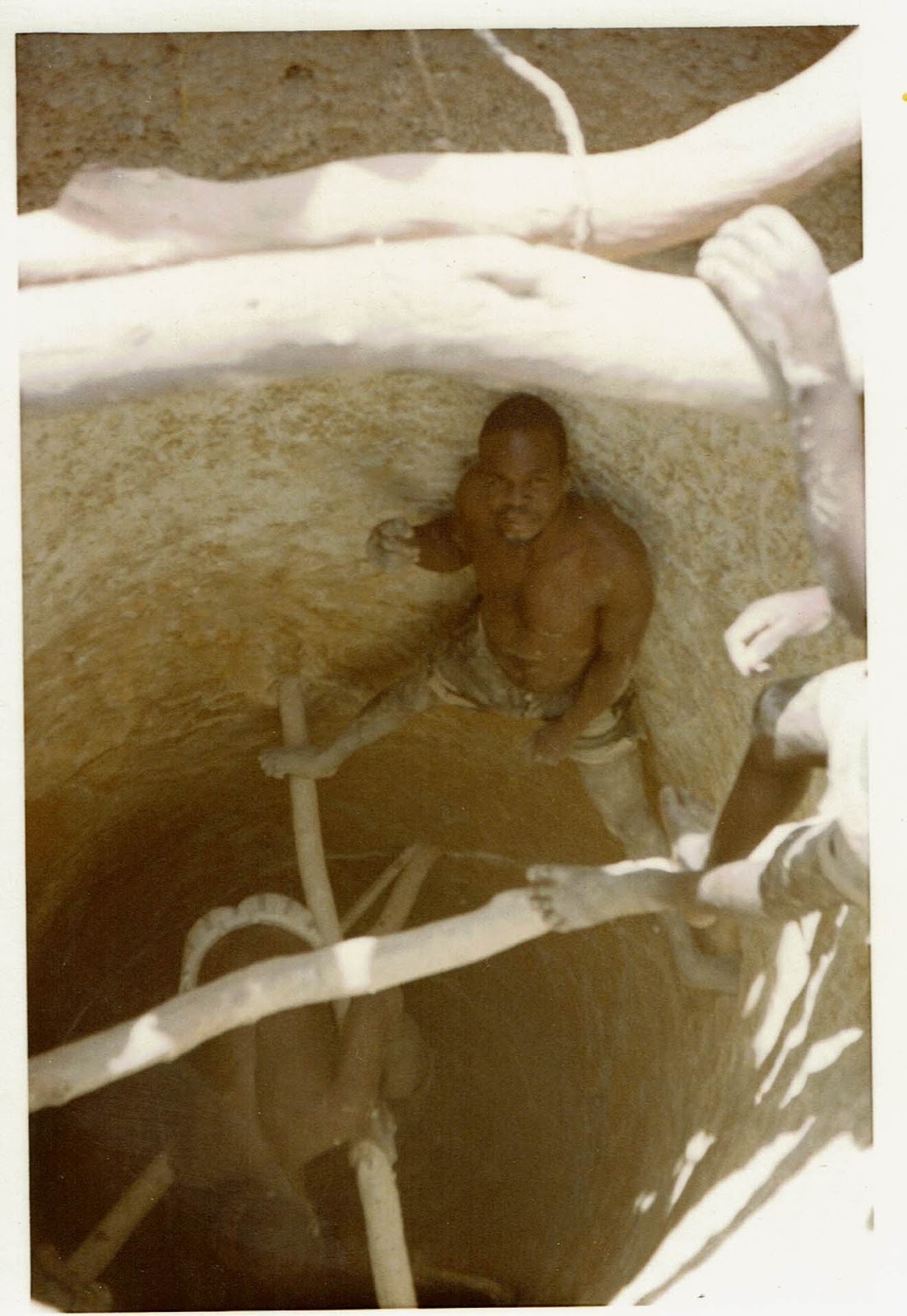

Speaking of going down into the well, you will need to do this occasionally to estimate how much extra cement you will need to patch up the cave-ins and to pretend you know what you are doing. If you decide to do this first thing in the morning be sure to practice your Mooré for “pull me up” in the likely case that a snake has fallen into the well overnight.

Other safety measures you should insist upon include providing hard hats for the well diggers. They will be filling buckets with soil, rocks, dead snakes, and eventually water, to be hauled up by hand, and then receiving concrete to be lowered in the same buckets, and it is guaranteed that there will be spillage, or worse, dropped buckets. The helmets will at least reduce the possibility of fatalities.

The trickiest part of the process is once you have hit water, digging deeply enough into the water table to provide an adequate supply, but not digging so deeply that you cannot bail it out to pour the concrete, or that it caves in. At this point it is a frantic race to bail it out, lower and assemble the three piece mold, and mix and pour the first meter of concrete. Inevitably this moment occurs late in the day and the next day is the beginning of Ramadan, so you end up working late into the night by lamp light and hope no snakes fall in.

The actual process of creating a one meter high, meter and a half diameter ring of concrete in a 20 foot hole in the ground is simple to describe and almost impossible to execute. First you have to build the reinforcing structure of steel rods. These ¼ inch 20 foot long rods are intended to provide a skeleton for the well, binding the concrete to the earthen walls, and the rings to each other. Ideally, you create a cage of two rings of re-rod attached to short re-rod stakes driven into the walls, and three vertical rods that attach to the rings. Once this structure is in place, the mold is lowered into the well and assembled, with a gap of 3-4 inches between the outer surface of the mold and the earthen walls of the well. The concrete is then mixed and lowered in buckets, and poured until the space between the mold and the walls is filled.

The reality of this effort is that you have two men in a hole in the ground about the size of a shower stall, trying to manage long lengths of very bendy re-rod. The mold, made of steel plate is very heavy, and coated with oil so the cement will not stick to it and is being lowered down to on a jury rigged pulley system by neighbors who may have a grudge against the diggers. The three pieces must be assembled and centered in the hole (it won’t do to have one side of the well 7 inches thick and the other side 1 inch). If this is the first meter of the well, the work is done standing in water.

All of the other sections are done while standing on a makeshift platform created by two pieces of angle iron supporting a couple of boards. Again, prayers that there are no fatalities are in order.

OK, so now the re-rod and mold are in place. You have dropped a plumb bob from the top of the well and the well is more or less vertical and it is time to make and pour the concrete. As one of our instructors told us while we made a practice well on the beach, make stew, not soup, meaning you need to get the proportions of sand, gravel, cement and water right. Doing this on a beach in Saint Croix is a bit different than on a well site in the Sahel. First, the sand and gravel have come to the site in baskets on the heads of women and children, from the bush where it has been swept up and gathered from dry washes (One of my fellow puisatiers tells of seeing a woman with a wheelbarrow that was part of our toolkit full of sand, balanced on her head). This aggregate certainly contains organic debris (goat dung is the hardest to detect as it looks like little pebbles, and after sitting in the sun for a while may be as hard), which you should try to minimize (get real, you are never going to get it all). Also, the water needs to be hauled up from the well and stored (a fifty gallon drum is handy for this- otherwise you will need a lot of canaries) .

By the way, before any of the above can happen you need to figure out how to get several hundred 50 lb bags of cement, re-rod, picks and shovels, a three piece mold, and other assorted implements to the well site. But even before you have to solve this problem you have to figure out how to get a truck load of cement delivered to you. It does happen, but probably not as soon as you need it, and when it does, you need to figure out how to keep it dry (the dry season does not mean it never rains), since wet cement is really just a big rock. If you are lucky enough to have one of the jeeps, you load it up like Jed Clampett’s truck.

If you don’t then you are going to have a line of villagers with stuff on their heads that will look like a Dr Livingstone expedition, hauling it all to the site.

As I mentioned I have only snatches of memory of actual wells that I was involved with, but some of these memories are quite vivid. On one occasion I put on my Mossi complet and rode my horse to a celebration of a completed well. I was quite a hit, but as this was the site where I got lowered into the well occupied by a large snake, this village was already quite used to being amused by me. Another completed well I recall visiting shortly before I COS’d, and being treated to a watermelon the kids had grown from seeds I gave them at the beginning of the well digging season. Although the pastek was not an unknown fruit, this particular watermelon was from seeds my mother had sent me, and it was sweet. My best memory of well digging however was when I visited the village of Lilougou in 1994, where John John and I had installed our first well, and had the pleasure of watching women pulling water from that well, watched over by Emile, the man who led the construction back in 1967.